We arrived in Medellín and instantly loved it. It is the country’s second largest city after Bogotá and sitting at 1495m in elevation, is the capital of Colombia’s mountainous province Antioquia, which is nicknamed the “City of Eternal Spring” because of its temperate weather. Everyday hovers perfectly between 24°C - 27°C, is mostly sunny, low humidity, and at night it usually rains, breathing life into the city’s green canopies and veil of surrounding mountain forests.

A view from the rooftop of our apartment

On our first day in Medellín, we arrived at our Airbnb at midnight, after taking an Uber from the airport through the túnel de Oriente, an 8.2km long tunnel cut through the mountains that connects the international airport with the city. The next morning we took a trip to the grocery store to stock our Airbnb where we would stay for the month, quickly adopting our meagre Spanish to navigate and communicate in a city where very little English is spoken.

In the afternoon we found the rooftop pool at our apartment, overlooking the vast valley of the sprawling city below, which also grew beyond the valley and up into the mountainsides in all directions above and around us. Medellín is a city enveloped by mountainous forest, both consuming it and being consumed by it. It’s unlike any city I’ve been - to be at a vantage point where the city extends both below and above you, where the skyscrapers in the distance are not obscured by those in front because they are perched on the edge of a mountainside higher above those below. It is exceptionally beautiful.

Making the most of the perfect weather, we developed a daily routine of having a swim in the rooftop pool of our apartment, followed by a sauna. The other activity that occupied most of our afternoons from about 3.00 - 4.00pm was waiting to get the perfect shot of the macaws that we learnt flew around our apartment every day at that time. There were 8 guacamayos that returned to the area everyday, on the lure of being fed by a lady from a nearby balcony. We would hear the first screech and then get the camera out and prepare for some shots.

Trying to catch the macaws in flight as they leave the balcony

Bird photography is exceptionally difficult and we have only just started learning, mostly through watching videos by Stefano Ianiro, an extraordinary bird photographer who makes beautifully presented and educational videos (and who also happens to be a little too good looking and charismatic for Dylan’s liking). Out of the thousands of shots, we managed to get a few that were good enough to keep. But we definitely need to keep practising.

Still working on how to focus when they're in flight

The apartment where we’re staying is in Poblado, the most affluent neighbourhood in Medellín and popular for tourists. There are cafes, restaurants, nightlife, shopping boutiques and upscale hotels and accommodation all enveloped by lush gardens, evoking a strong sense of living in a tropical rainforest.

A waterfall running under the streets of the lush rainforest throughout Poblado

Our apartment is a 20 minute walk up the hill from the centre of activity in Poblado. The daily walk up, combined with the high altitude, provides good cardio training. I also joined the F45 in Poblado. At first the classes that would be difficult for me in Sydney felt nearly impossible; trying to take in oxygen felt unusually painful and the incremental lack of oxygen made my head spin. But after a regular routine (and walking back up that hill afterwards) I’m sure I’m the fittest I’ve ever been. The staff there were so friendly and there was a regular group of us going to the 10am class - some expats, some locals and a few like me, dropping in while travelling - a little community having fun excercising together and speaking spanglish.

The F45 in Poblado

On our second day, Dylan set to work and I went on a coffee farm tour I found through Airbnb experiences. After finding the host, Laura, and joining a small group of 5 guests at the agreed meeting place, we took 2 taxis to the farm, a 15 minute drive along a mountainside of steep, narrow and winding roads. Arriving at the farm, we were greeted with hugs from our host’s mother along with a slice of chocolate cake and a traditional Colombian drink of aguapanela, a cold and refreshing sugarcane juice.

The coffee house at Laura's family farm

We were then dressed in the traditional outfit of the female coffee collector or chapolera with a hat, poncho and collecting basket tied around the waist. The family has been making coffee for 200 years and the whole process is carried out at their farm, collecting berries by hand and using simple traditional tools for washing, grinding and roasting the coffee beans.

Laura passionately explained the history of their farm and the stages of coffee production, from planting the trees, collecting the ripe fruit, sorting and washing the fruit, peeling it to reveal the coffee bean, and then drying, roasting and grinding the beans. Her and her family, like most people in Medellín, do not speak English and so she spoke Spanish and had a translator-turned friend, translating her story telling into English for those guests who needed the translation. It was a great way for me to practise by hearing it first in Spanish and then the translation. I tried to speak Spanish as much as I could during the day, practising with the guests who did not speak English.

Me dressed as a chapolera picking coffee berries

After our immersive experience through the coffee farm, we sat for a traditional peasants lunch called sudado de pollo (or sweaty chicken) cooked for us by Laura’s mum. To complete our tour, we had a tasting of the four varieties of coffee they make at the farm - natural, fermented, honey, washed - as well as a tea made from coffee berry skin. My favourite was the honey, and so I purchased a bag to enjoy for our morning coffee back at the Airbnb.

Sweaty chicken lunch

Later that week we went on a street food tour in Poblado. On our first day in Medellín, after we’d picked up our groceries, we had stopped at a food stall to grab a quick lunch. We’d managed to order a variety of empanadas and other similar foods but weren’t really sure what we were eating and so we decided we needed to learn more about the typical foods. On the tour, we spent a couple of hours walking around Poblado, tasting Colombian street food and learning about the history of the foods and their preparation. Arepas are the quintessential food of northern South America (eaten not just by Colombians but also Venezuelans). They are sort of like a very thick tortilla and similarly stuffed or topped with various ingredients.

Arepa with pork belly

We tried a corn and flour blended arepa cut open and stuffed with crispy pork belly, a corn arepa topped with butter and cheese, and empanadas with beef and chicken. I quite liked the corn arepa with melted butter on top, but the cheese they also laid atop - a kind of flavourless haloumi - was rather weird. During the tour we also visited a rooftop bar with a spectacular view of the city lit up at night. Rooftop bars are very popular in Poblado and most also have a simming pool. Interestingly, they don’t seem to be concerned about mixing glass, drunk people and pools here! During our stay we went back to the first arepa place for lunch to try some of their different fillings. My favourite was the mixta which has chicken, meat, melted cheese and hogao, a traditional Colombian sauce made with tomatoes and onions.

Learning about corn arepas - arepa de chocolo

Overall though, we found the traditional food to be quite bland. We thought the food might be similar to Mexican food but it has nowhere near the flavour and variety of that cuisine. But it is always good to experience local foods and understand why they have came to be that way. However, we did eat some good food as we got a bunch of restaurant recommendations from a local. A friend of mine is Colombian and she put us in touch with one of her friends living here in Medellín. Unfortunately we didn’t get to meet her because she had to fly to Bogotá the day after we arrived, but we stayed in touch over messages to get lots of tips and recommendations. The best restaurants we ate at were Alambique, Cafe Dragon, Halong and oci.mde. We also managed to figure out the food delivery service Rappi to get pizza delivered one night.

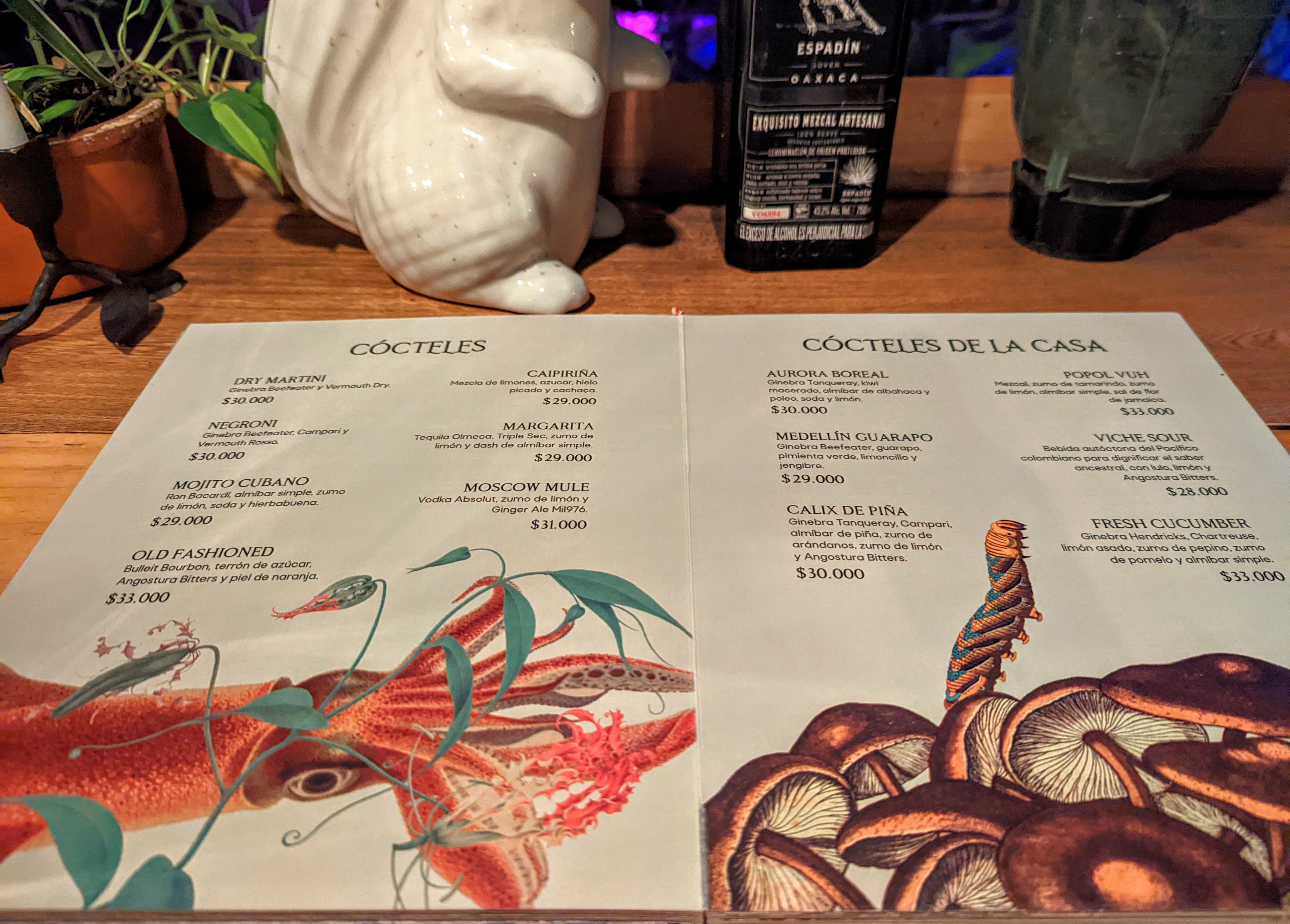

The Alambique menu was a beautiful hard cover book displaying delightful drawings of animals and plants

At the end of our first week in Medellín we took a weekend trip to Guatapé, a small resort town high in the Andes, famous for its colourfully painted houses and la Piedra, a large granite monolith sitting high above the surrounding landscape.

A view of la Piedra from the town of Guatapé

To get to Guatapé, we took a bus from the bus station in Medellín. We were a little apprehensive about taking the bus, but I read a detailed blog post with instructions on how to do it and in the end it all went smoothly. It was a 2 hour trip out of the city and further into the mountains. Every now and then the bus would stop and pick up local passengers who would sit in the aisle or on the steps, as well as the occasional street vendor who would jump on temporarily to sell snacks. We arrived in town late morning and wandered around looking at the brightly coloured murals painted on all the buildings.

In the streets of the brightly coloured town of Guatapé

The scenes depicted on the facades sometimes reflect its occupants; the bakery has a baker and bread, the coffee shop has a cup of coffee and the farmer, a farming scene, and so on. They are well-maintained and as we explored the town we frequently saw the buildings and murals being repainted with fresh paint. Some of the common designs showed llamas, flowers, tropical birds and corn. At the centre of town is a street filled with brightly coloured umbrellas strung along the street providing a canopy of colour. All over town there are injections of colour everywhere. You can’t help but smile at the endless rainbow of colour.

A colourful mural of llamas

For lunch we went to a highly rated restaurant I found called El Bacchanal where we had incredibly good burgers. We got chatting to one of the co-owners who was there and found out that he and his Australian business partner started the restaurant/bar during the pandemic after they got stuck in Guatapé. They have spent a lot of effort creating a good menu and training staff to make consistently good food, and it is paying off for them. After 2 years they are still in business and the place gets packed. He invited us to come back that night for live music and cocktails, which we did, but first we had to go climb la piedra, the rock.

Lunch at El Bacchanal

To get to the rock we took a motochiva (also known as a tuk-tuk or auto rickshaw in other countries). The motochivas provide transport in and around Guatapé. The drivers take great pride in their vehicles and like the buildings in their town, have them painted in bright colours and often with a theme. We had spotted a pink “La Barbie” themed motochiva earlier in the day that I was desperate to take a ride in to the rock, but he wasn’t around when we were trying to go. But we found another good one decked out in bright colours. The drive to the rock is a 20 minute hair-raising ride, bumping along the pot-holed roads at a decent speed without seatbelts or doors in the tiny three-wheeled vehicle.

The motochiva we took up to the rock

A masonry staircase has been built into a vertical crack on the northern face of the enormous granite boulder, providing a pathway of 649 steep steps to the top of the rock, from which there are spectacular 360 views of the surrounding countryside.

A view from the top of the rock

Sitting at 2150 metres above sea level, I was not sure whether the exhaustion and lightheadedness I felt during the ascent was my lack of fitness or the actual decrease in oxygen at that altitude. Either way, the momentary discomfort was well worth it for the panoramic vista that greeted us at the summit. After taking a breather and some photos, we descended and then sat at a cafe at the base of the rock to watch the sun set before taking another motochiva back into town.

Watching the sun go down

We had a shower at the Airbnb before dinner at a hostel serving Thai food, and then headed back to El Bacchanal for the night. We got the last two seats, at the bar, and settled in for the night. The musicians were fantastic, belting out all the best classic songs, seamlessly switching between those in spanish and those in english. The cocktails kept coming until finally the music stopped and we headed back to our accommodation at midnight. It was a really fun night, confirmed by my hangover the next morning.

El Bacchanal bar

One of the bartenders had given us a recommendation for breakfast and it did not disappoint. We otherwise wouldn’t have found this cafe, selling real sourdough bread and all the kinds of things you want for breakfast when feeling dusty. It can be very hard to find western-style breakfast in Central and South America and it was very satisfying to munch on a toasted croissant filled with bacon, egg and cheese.

Croissant breakfast at Cafe de Ciclistas

After breakfast we went to find someone who would take us on a boat tour around the lake, which has been partly formed by large-scale damming when a large hydroelectric complex was built there in the 1970s. We had tried to book something online, but couldn’t find anything and so we went straight to the boats instead. We asked the first guy we saw near a boat, negotiating in bad spanish for an hour’s ride around the lake.

And so we clambered into a little dinghy, but it wouldn’t start. The driver kept trying to start the engine, the failing throttle increasingly letting out more gasoline-scented smoke, but after too many failed attempts for our comfort we asked for another boat. The guy we paid for our tour went to find the driver of another boat, but after clambering into a dingy dinghy once more, it turned out this guy was also having trouble starting his. Sitting there, life vests on, we looked at each other smirking, wondering if our boat ride was not meant to be. But just as we were considering abandoning the whole idea, the driver got it going and we were off. The boat driver-cum-tour guide rattled off information in rapid spanish about the things we were passing by, us politely nodding, catching the odd thing he said here and there.

In our dinghy on the lake, the rock in the background

We arrived back at the dock an hour later, a little wet, but content with our lake tour. Afterwards, we wandered around town a little more, ate lunch, and then bought return bus tickets and headed back to Medellín.

A favourite spot in Guatapé is the street of colourful umbrellas

During our time in Medellín we did a few more tours. One night after Dylan finished up work we went on a cocktail and fruit tasting experience at one of the many rooftop bars in Poblado. We were the only ones there and so we had a private experience of tasting exotic Colombian fruits and then making our own cocktail creations with them. There is a unique citrus growing here that is a mandarin-lime hybrid, which is a fun sour alternative to the traditional lime or lemon used in most cocktails. The host had also pre-prepared a number of delicious syrups from fruits so we used those along with the fruits and spirits to make some unique creations.

Sampling Colombian fruits during our cocktail experience

But by far the most interesting tour we did was our tour of Comuna 13 and the city centre. Our guide, Sebastian, runs tours through his company Colombian Ambassadors. He used to be an architect and run tours on the side, but he can make more money as a tour guide and so now does tours full time. We met up with our group in the centre of the city for the start of our tour, titled From violence to innovation, which would take us through the city over 4 hours to learn how Medellín trandformed from being the city with the highest murder rate in the world to reducing murder rates by 95% in only 20 years. The epicentre of that crime, and the most transfomed part of the city is Comuna 13. As late as 1991, Medellín was still in the hands of the Medellín cartel and in Comuna 13, a murder was occuring almost everyday.

A safe and revitalised Comuna 13

An integral part of our tour was using the city’s public transport system because the city’s transformation from one of extreme violence to the safe tourist destination it is today was driven, in large part, by the introduction of public transport. The metro system in Medellín is the cleanest I have seen anywhere in the world; there is no graffiti or rubbish or any damage to the trains at all. It is impeccably pristine and very safe. The commuters form an orderly queue and wait patiently while passengers alight before they board the car. Everyone is respectful and there is no crime on the metro. Perhaps the only other place I can think of that has a public transport system of comparable cleanliness and order is Singapore, but in contrast to the austere culture driving compliance there, the compliance in Medellín has been formed by a culture of pride and love for their transit system. They can see how it has revolutionised their lives and it is not taken for granted.

Medellín is a city located in the Andes. The city centre is in a valley and the city sprawls upwards in all directions from there. The city’s poorest live high up in the hills, removed from the infrastructure and commerce of the city centre. The decades of drug wars caused the dislocation of millions of Colombians from rural areas into the city. These people have built their own housing; fragile structures clinging perilously to the sides of the steep terrain, always at risk in the tropical wet environment from landslides. The roads only went so far and as make-shift housing accumulated, the only way to get to the top was by walking up steep staircases, frequently built by the very same people using them.

Make-shift housing built onto the sides of steep terrain, now connected to the city via a gondola

It was not practical to build roads or trains up to these remote areas of dense housing and so the Government built gondolas. It was the first place in the world to use gondolas as a form of public transport rather than for transporting tourists to lookouts or skiers to the top of ski runs.

Fundamentally, the novel use of gondolas as public transport provided access for these mountain dwelling communities: access to work, school and education, and access between areas of the city which had been near impassable before. The gondolas cut the one-way journey time from parts of these isolated mountainside neighbourhoods to the city centre from 3 hours to less than 30 minutes. The introduction of public transport coincided with a significant reduction in crime by creating a more interconnected city, first by overcoming the isolation and then by providing opportunities for residents to access school and employment.

One of the city's gondolas

In Comuna 13, outdoor escalators were also built in the small spaces between houses, significantly reducing the physical effort required to be expended to ascend the sharply rising neighbourhood, enabling the transport of people and the goods they need to take to their home, dramatically easier.

Escalators in Comuna 13

Without access and interconnection to the rest of the city, young people could not get to a school, and so many resorted to the only other source of income that was available to them - working in the drug-related gangs that ran their neighbourhoods. It created a vicious cycle of violence. Facilitating access broke down the physical barriers to other opportunities and, along with other Government interventions at that time, it transformed these crime-ridden comunas into the vibrant and safe communities they are today. It seems too simple to believe but the introduction of transport transformed these neighbourhoods and the lives of their residents.

Graffiti art in Comuna 13

As the crime reduced, and access opened up, the inhabitants expressed their safety and freedom through art and music, which is most evident in the walls of graffiti along the paths of the escalators. Comuna 13, once known as the murder capital of the world, is now a tourist hotspot filled with street art, performers and outdoor bars.

Graffiti art in Comuna 13

We were so fortunate to learn about the history and radical transformation of this community from a local who lived through the most violent years in Medellín. The change is extraordinary and I imagine this captivating city will only become more and more enticing as it continues to evolve and embrace tourism.

Graffiti art in Comuna 13

We’ve loved our time here in Colombia and could easily return one day. Tomorrow we’re off to Costa Rica to spend a week meeting up with some of Dylan’s work colleagues. They have planned some rainforest trips where we are hoping to see sloths. We’ll come back to Medellín afterwards, but only for a few days, before we then leave for Ecuador. We’ll ascend to nearly 3,000m in Quito where we’ll spend 5 days before returning to sea level for our highly anticipated trip to the Galapagos.