It’s hard to know even where to begin with describing New Orleans, Louisiana. NOLA.

It is unlike any other city in the US. It’s hard to put your finger on exactly what makes it so unique but when you learn that the food, music, architecture and language has been influenced by French, Spanish, native American, Caribbean and West African cultures, you start to understand how this beautiful melange created the place it is today.

Mardi gras beads hanging in the tree in the Garden District

Arriving in August, it’s hot and steamy. The airport doors slid open and we stepped outside into the sticky air. It was 32°C and 90% humidity. They were experiencing cooler than normal weather due to all the rain. We got picked up in a Tesla Uber and rode to our Airbnb in the Bywater area, where Mum and Brian were already waiting, air conditioning on and beers in the fridge.

While we were in New Orleans, we took a lot of Ubers because we were staying too far to walk from the places we were going, and also, 5 minutes walking rendered one disgustingly hot and sticky. We always made mum sit up the front because she’s the chatty one. She would ask evey driver the same string of questions and we’d learn more about the city and its people with each answer. Like that they had all lived in New Orleans their whole lives, except for when they evacuate to Houston from hurricanes. On evacuation, we talked to one guy who said he only evacuates for category 3 and above, and a lady who (perhaps jokingly but half serious) said she now evacuates at the first sign of a storm, after not making it out during Katrina. But to mum’s question, ‘What is the best thing about New Orleans’, the answer was always the same: the food.

You can’t talk about NOLA without talking about food. Its food is an eclectic blend of the city’s cultures, all thrown together in the soup pot, riffing off each other, adding and subtracting what was readily available in a blend of French, Spanish, Creole and West African cuisine.

Wandering through the French Quarter

After we settled into the Airbnb, and I showered off the sweat of the lady who sat next to me on the flight, we headed into town for drinks at a few cocktail bars before dinner.

Perhaps almost as equally synonymous with New Orleans as the food are the cocktails. The city is steeped in cocktail history and many classic drinks still consumed today were invented in New Orleans. We went to Loa bar and then The Sazerac Bar, located inside the historic and ornate Roosevelt Hotel. Even if you don’t go to the bar, it’s worth a squiz inside the hotel lobby.

There is not a lot of evidence on the early history of cocktails and so there are different theories about firsts and origins. We do know that the word ‘cocktail’ appeared in print as early as 1798 in London and 1803 in the US. But some consider the Sazerac to be one of the world’s earliest mixed drinks, invented sometime in the 1830s in New Orleans. In recognition of this special history, it was named the official drink of New Orleans in 2008. So, I had to have a Sazerac at The Sazerac Bar. Dylan ordered a Ramos Gin Fizz, a labour-intensive drink first made in 1888 by Henry Ramos also in New Orleans (although it was originally called the New Orleans Fizz and later renamed after its creator).

At The Sazerac Bar with a Sazerac and Ramos Gin Fizz

We then went for dinner at Cochon, a restaurant specialising in pork and cajun dishes. I had my first gumbo of the week and a delicious mac and cheese, fulfilling a craving I’d had since our arrival in the US. For dessert, mum and I shared a chocolate chess pie served with toasted marshmallow flavoured ice-cream and a malt crumb. It was so damn good that despite feeling very full already, we finished it all, every last malt crumb. It was gone so quick I didn’t even get a photo. In fact, I realised as I tried to put photos in this blog post that I have very few photos of the food we ate. It would arrive and we’d consume, realising I forgot to capture it when there was an empty plate in front of me.

A bad photo of my gumbo at Cochon

The next day, mum, Brian and I went on a swamp cruise in the morning while Dylan remained at the Airbnb to work. We learnt all about life on the swamp, in the moments we could actually make out the words camouflaged in our tour guide’s heavy southern drawl.

An alligator on the swamp tour

We heard about the life of an alligator hunter, the city’s losing battle against the seasonal surge of the mighty Mississippi, and the increasing loss of the Mississippi River Delta and coastal Louisiana. Historically, the annual spring flooding of the river enabled the river to cast its sediment across the flood plain, thereby creating solid ground and replacing the sediment that is lost through natural erosion and storms each year. But harnessing the river with levees and flood walls prevents the sediment from reforming the coastline and instead, it is washed out into the Gulf of Mexico. A football field’s worth of wetlands vanishes into open water every 100 minutes, and the threat of rising sea levels only increases the risk of New Orleans becoming completely submerged. Already half of the sinking city sits below sea level and some scientists predict it may only be 30 years before the entire city is submerged. After hurricane Katrina the city remained inundated for 3 weeks because the water had nowhere to drain.

A boat overturned by hurricane Ida in August 2021

On the swamp cruise we saw some alligators, drawn to the boat with the lure of marshmallows. The guide also pulled out a baby alligator somewhere from the back of the boat to be passed around the group. I felt somewhere on a blurred line between being in nature and at a zoo. But she was pretty cute.

Brian holding the baby alligator

We took an Uber back to the French Quarter to get our obligatory beignets at Cafe du Monde, the original French coffee market since 1862, serving those delightful fried donuts smothered in a mound of fluffy icing sugar. I was worried it would be one of those experiences where the actual event pales in comparison to the anticipation, but it wasn’t. They were delicious and I devoured my paper bag of three beignets, leaving only a dusting of white powder all over my lap.

A Cafe du Monde beignet

Afterwards, we met Dylan for lunch at Mother’s Restaurant for po’ boys; the soul of New Orleans culinary culture. The ‘poor boy’ sandwich is made from a French baguette filled with mayonnaise, lettuce, tomato and a protein, traditionally roast beef, fried shrimp or oyster. It is essential New orleans eating.

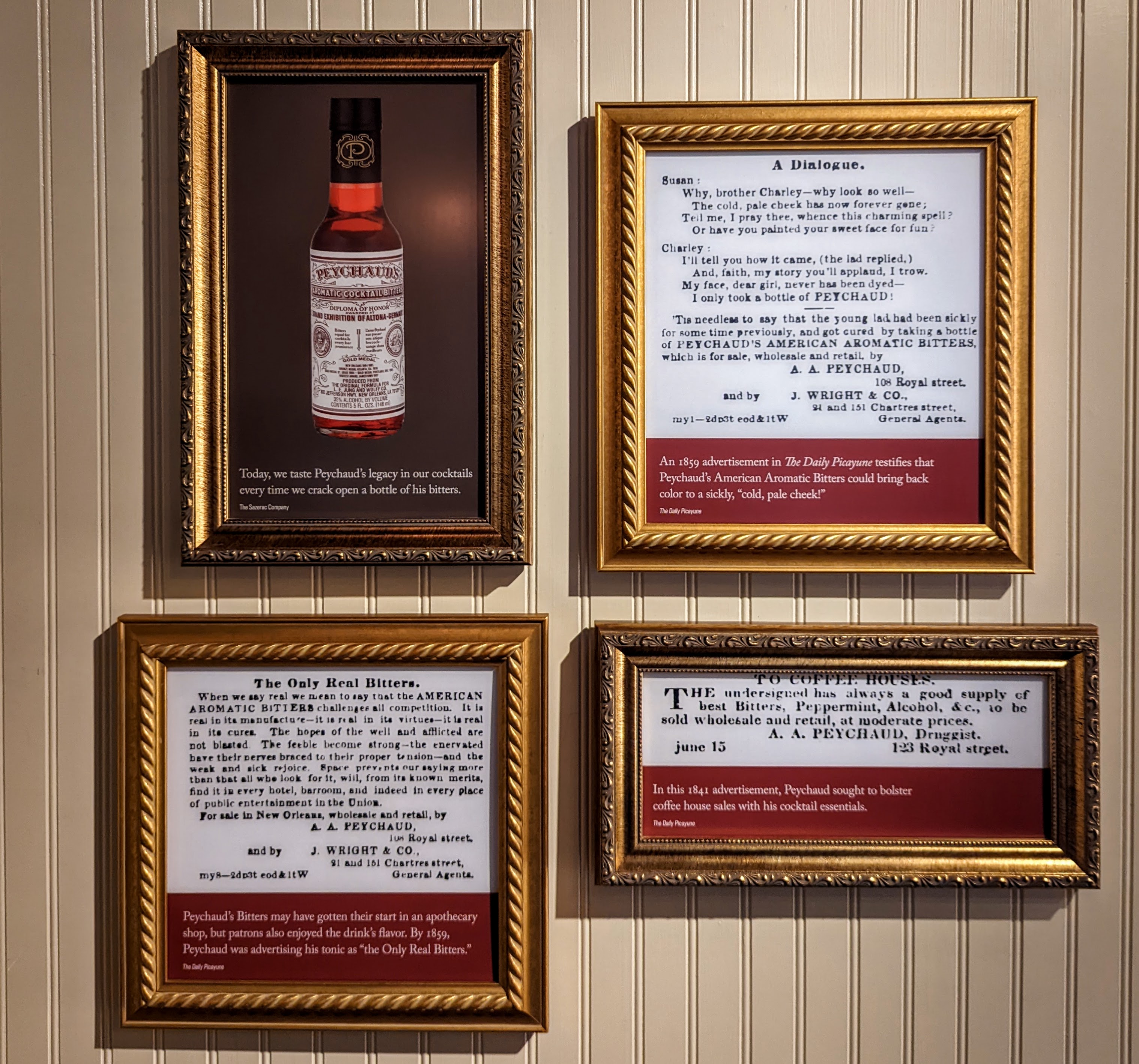

After lunch, we enjoyed a complimentary tour of Sazerac House, an interactive museum of New Orleans cocktail history. Sazerac House opened in the French Quarter in 1852 as a coffee house. Coffee houses were meeting places mimicking the same European establishments, but unlike their European counterparts, the ones in New Orleans served alcohol. During the self-guided tour you can read all about the history of New Orleans drinking and especially the origins of the Sazerac cocktail. The experience also includes three cocktail demonstrations and tastings, one of which is the Sazerac. A Sazerac is made with:

- cognac or rye whiskey

- Peychaud’s bitters

- absinthe or Herbsaint

- sugar

There is debate over whether a Sazerac should be made with cognac or rye and with absinthe or Herbsaint. I’ll explain a little about why that is below.

A good place to start the story of the history of the Sazerac is with Antione Peychaud himself, who settled in New Orleans in 1795 from the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Soon after that, in the early 1800s, the Sazerac de Forge et Fils brand of cognac was introduced into Louisiana. New Orleans was French until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and had a lot of French influences. During this time people would have been drinking cognac “cocktails” (probably just a simple mix of spirit and sugar) but whiskey would also have been available because Louisiana was now American. Cocktails didn’t start becoming named drinks until the 1860s and so before that, patrons would have simply ordered a category of drink, like a “brandy cocktail” or a “whiskey cocktail” at the coffee house.

A bottle of Sazerac cognac

In 1834, Peychaud established an apothecary that sold bitters to local coffee houses. At that time, the coffee houses therefore would have been serving a “brandy cocktail” with Sazerac cognac, Peychaud bitters and sugar. The Sazerac House is one of those coffee houses.

In 1885, there was a phylloxera outbreak in French vineyards, meaning cognac was in short supply or very expensive. While there is some debate over this point, some cocktail historians suggest that the bartenders at the Sazerac House began to make that same brandy cocktail with rye whiskey instead. It is possible though that both a whiskey and cognac version could have been sold concurrently. In any case, it seems generally agreed that the Sazerac House popularised some version of this cocktail, and its connection with the venue may later have resulted in the drink being called a Sazerac.

Later, in the mid to late 1800s, bartenders started adding popular modifiers to their drinks. The common ones at the time were absinthe, maraschino liqueur and curaçao. At some point here then, absinthe was added to this popular cocktail sold at the Sazerac House. Absinthe was probably used due to the city’s lingering Frenchness and the aniseed flavour profile, which complements the delicate aniseed taste in Peychaud’s bitters.

A collection of posters inside the Sazerac House museum

The absinthe was later replaced with Herbsaint, which was created by J. Marion Legendre in the 1930s as a substitute for absinthe after it was banned in the US un 1912. Absinthe was not allowed again in the US until 2007. The Sazerac was made originally with absinthe and therefore some people believe it should now be made with absinthe. However, the drink was popularised and made for a long time with Herbsaint, and so others believe it should continue to be made with Herbsaint. In New Orleans, it is almost always made with Herbsaint.

Inside Sazerac House

On the spirit, most recipes today will call for rye whiskey. But a perfectly acceptable alternative is to order it with cognac, or another alternative, which I’m rather partial to, is a half-half mix of rye and cognac; a nod to the entire history of this humble drink.

The Sazerac cocktail

Before dinner that night, we went for a cocktail at Jewel of the South, an exquisite restaurant and cocktail bar serving an innovative and refined menu. I had their brandy crusta, another classic cocktail of New Orleans, invented in the same restaurant sometime in the 1840s or 1850s. It was perfection. All our drinks were divine and we were tempted to stay for dinner, but we headed instead to Original Pierre Maspero’s to try the jambalaya. The French Quarter restaurant is located in a historic building built in 1788 and serves up classic creole cuisine.

Cocktails at Jewel of the South

After dinner we went to Beachbum Berry’s Latitude 29 tiki bar. The holy grail of tiki bars. Its owner was an historian of tiki culture and is credited with researching and recreating the lost tiki cocktails from the fading tiki era created at the famous tiki bars Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic’s. The owners and bartenders of the tiki era held their drink recipes as closely guarded secrets; Donn Beach famously kept the actual recipes secret even from his bartenders. As a result, poor imitations of classic drinks like the mai tai and zombie became common. Berry set out to rediscover or reverse-engineer the original drinks and did so successfully. He opened his bar in New Orleans in 2014. He also made his own creations, some of which are kept secret today. One is the delicious drink named for the bar, the Latitude 29. When we asked for the recipe, the waitress told us that they’ve signed NDAs for this cocktail’s recipe. But we know the ingredients and so we’ll try some reverse engineering ourselves when we get home!

The Latitude 29 at Beachbum Berry's Latitude 29

The next morning we did a great walking tour of the Garden District, learning more about the history of New Orleans and this district’s rich and famous residents, both former and current, and their spectacular houses. After the tour, we took a reprieve from the heat inside Tracey’s bar for lunch, and later enjoyed an amazing ice-cream at Sucré, and then some browsing through the eclectic boutiques of Magazine Street.

The Garden District

In a familiar state of hot and sweaty, we took the Charles Street streetcar back to the French Quarter for a little more exploring and then soon after, an Uber back to the Airbnb for a swim and shower.

One of the original New Orleans beautiful water meter covers in the Garden District

Before dinner, we headed back to the French Quarter to grab a hurricane to-go from Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop Bar, which has been serving drinks on Bourbon Street since the 1700s. One of the unique things about New Orleans is that you are allowed to drink in the streets, and so bars provide take-away drinks. Bourbon Street is the epicentre of this frivolity.

The hurricane is another New Orleans invention, originating in the 1940s at Pat O’Brien’s bar. During WWII, whiskey was hard to come by and so distributors often required large purchases of rum, which was not popular, in order to get whiskey. The story goes that the recipe, which uses up to 4 ounces of rum per drink, was intended to get rid of the excess rum quickly. With some juice added it goes down far too easily!

Our hurricanes on Bourbon Street

We walked with our hurricane in hand down the length of Bourbon Street, but one lap of that chaotic party scene was enough for us oldies, and so we grabbed an Uber to dinner.

For our last night together we had dinner at Gabrielle, an unpretentious but refined restaurant serving cajun food with a strong French influence. The food was exquisite, the cocktails and wine delicious, the service impeccable, and the company delightful.

A beautifully presented jambalaya at Gabrielle restaurant

It was the perfect experience to end our time in NOLA; the food the centre of the experience, bringing people together, creating a moment in time where the meal becomes etched in the collective memories of the diners who shared that moment.